I first read this many years ago and decided to re-read it again after I finished Rudyard Kipling's Kim with my book club.

The subtitle, A Year in Delhi tells you pretty much exactly what you get - an account of Dalrymple and his wife's time in Delhi. Like most travelogues, this book features a few of the trials and tribulations associated with travel and living in a new place, but it offers much more than that. During his stay, Dalrymple delved into the history of the city, and the reader is treated to a book that weaves back and forth in time, telling us what the city as like way back when, an then revealing it again in 1993.

He covers a wide variety of topics, from historic people and places to the state of modern eunuchry, partridge fighting, and sufism. And the book has some great characters, like partridge aficionado Punjab Singh (whose name is surely an Indian version of Indiana Jones) and the archaeologist B.B. Lal. For a GM like me who likes to infuse their made up worlds with the verisimilitude of the real world, these characters are inspiration gold. It's these characters and some of the situations they find themselves in that I'd like to share with you here today.

One of the more interesting characters in the book is Pir Syed Mohammed Sarmadi, a very successful fraudulent dervish. Dalrymple describes him as -

One of the more interesting characters in the book is Pir Syed Mohammed Sarmadi, a very successful fraudulent dervish. Dalrymple describes him as -

"A hugely fat sufi with a mountainous turban, and elephantine girth, and a great ruff of double chins, he operates one of the most profitable faith healing businesses in India. One of Sarmadi's forebears was beheaded by the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb after he wandered into the imperial presence stark naked, shrieking out sufi poetry."

"Everyday, Sarmadi sits cross-legged in his surgery between ten and five, with a short break for a kebab at lunch. It is a small room, and Sarmadi fills a great deal of it. Its walls are lined with powders and sacred texts, framed monograms of Arabic calligraphy and pictures of the Ka'ba at Mecca. There is a continuous queue of folk waiting to see him, and Sarmadi keeps the queue moving. Each petitioner gets about two minutes of his time. Sarmadi will listen, breaking his concentration only to clean his fingernails or to gob into his golden spittoon. When finished, Sarmadi will wave his peacock fan and blow over the petitioner, recite a bit of the Quran, write out a charm or a sacred number, and place it in an amulet. He will then dismiss the supplicant, having first received his fee of fifty rupees, a week's wage for an Indian labourer."Sarmadi seems to come from a long line of such Sufis, so with a little research, one could round fill out a full faction of them: https://reflectionsofindia.com/2014/07/22/sufisarmad/

Dalrymple also relates some of the stories of past visitors, like Dargah Quli Khan, who visited the city between 1737 and 1741 and reports on the local orgies:

"Hand in hand, the lovers roam the streets, while [outside] the drunken and debauched revel in all kinds of perversities. Groups of winsome lads violate the faith of the believers with acts which are sufficient to shake the very roots of piety. There are beautiful faces as far as the eye can see. All around prevails a world of impiety and immorality. Both nobles and plebeians quench the thirst of their lust here."Dalrymple later reflects on the modern city:

"Modern Delhi is thought of either as a city of grey bureaucracy, or as the metropolis of hard-working nouveau riche Punjabis. It is rarely spoken of as a lively city, and never as a promiscuous one. Yet, as I discovered that in December, the bawdiness of Safdar Jung's Delhi does survive, kept alive by one particular group of Delhi-wallahs. You can still find them in the dark gullies of the old city, if you know where to look."Through Dalrymple, we are exposed to the 17th Century writings of Niccolau Manucci, son of a Venetian trader who ran away from home at 14 to become a con artist, trickster, and artilleryman in 1660's India. It is partly through his eyes that we learn of Shah Jahan and his in-fighting children Dara, Aurangzeb, Jaharana, and Roshanara.

Of Aurangzeb, he says:

And Dalrymple tells us of Ibn Battutah, who resided for 8 years in Delhi in the 1330's and 40's with Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluk as a patron. Now, the sultan was a complete bastard (in a pique of anger at the citizens of Delhi, he once gave the entire citizenry 3 days to completely remove themselves to another city 40-days walk away, and when a blind man and a cripple were found still in the city, he had one ejected by catapult, and the other dragged to the new city behind a horse (only his leg arrived). But the sultan liked Battutah (mostly) and at one point decided to send him on a diplomatic mission to China.Battutah found himself at the head of an entourage of 1000 mounted bodyguards and a long train of camels carrying gifts, such as 100 concubines, 100 Hindu dancing girls, gold candelabras, brocades, swords, and gloves embroidered with pearls. Behind the camels came the most valuable gift of all - a thousand thoroughbred horses from Turkestan.

But only 100 miles into his journey, his train was attacked by Hindu rebels (the country was full of rebels) and Battutah was separated from his group and captured. He managed to escape and re-join his party. At Calicut on the Malabar coast, he loaded everything onto four dhows to sail to China, but lingered on shore for Friday prayers. A sudden storm blew up, grounding and breaking up the boats. The slaves, troops, and horses all drowned. Not daring to return to Delhi, he hightailed it to China on his own.

" Although Aurangzeb was held to be bold and valiant, he was capable of great dissimulation and hypocrisy. Pretending to be an ascetic, he slept while in the field on a mat of straw that he had himself woven . . . He ate food that cost little and let it be known that he underwent severe penances and fasting. All the same, under cover of these pretenses he led a secret and jolly life of it. His intercourse was with certain holy men addicted to sorcery, who instructed him how to bring over to his side as many friends as he could with witchcraft and soft speeches. He was so subtle as to deceive even the quickest witted people."

And Dalrymple tells us of Ibn Battutah, who resided for 8 years in Delhi in the 1330's and 40's with Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluk as a patron. Now, the sultan was a complete bastard (in a pique of anger at the citizens of Delhi, he once gave the entire citizenry 3 days to completely remove themselves to another city 40-days walk away, and when a blind man and a cripple were found still in the city, he had one ejected by catapult, and the other dragged to the new city behind a horse (only his leg arrived). But the sultan liked Battutah (mostly) and at one point decided to send him on a diplomatic mission to China.Battutah found himself at the head of an entourage of 1000 mounted bodyguards and a long train of camels carrying gifts, such as 100 concubines, 100 Hindu dancing girls, gold candelabras, brocades, swords, and gloves embroidered with pearls. Behind the camels came the most valuable gift of all - a thousand thoroughbred horses from Turkestan.

But only 100 miles into his journey, his train was attacked by Hindu rebels (the country was full of rebels) and Battutah was separated from his group and captured. He managed to escape and re-join his party. At Calicut on the Malabar coast, he loaded everything onto four dhows to sail to China, but lingered on shore for Friday prayers. A sudden storm blew up, grounding and breaking up the boats. The slaves, troops, and horses all drowned. Not daring to return to Delhi, he hightailed it to China on his own.

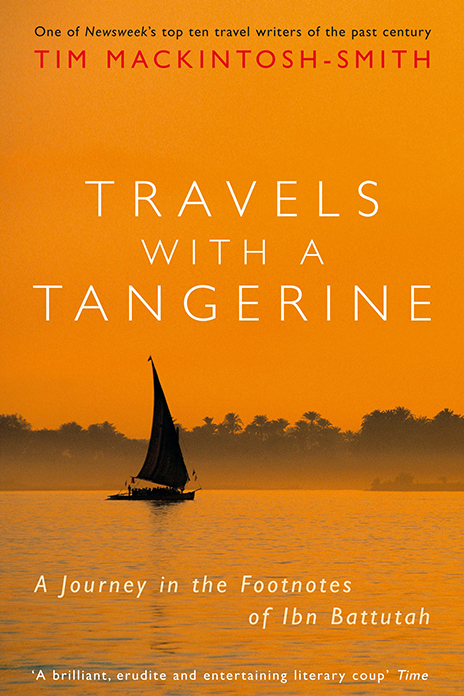

I'll return to Ibn Battutah in a future post, and maybe we'll also look at another travel writer - Tim Mackintosh Smith - who not only wrote an annotated translation of The Travels of Ibn Battutah, but also Travels With a Tangerine: A Journey in the Footnotes of Ibn Battutah.

As for Dalrymple, he's an evocative writer and I found this book a pleasure to read. It won two awards, has been adapted into a play, and (I'm quite sure, though it doesn't say so on Wikipedia) was turned into a television series in the UK. Here's the Wikipedia page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/City_of_Djinns